We are releasing sections of the book The Process Safety Professional to our subscribers. We are currently working on the second part of Chapter 6 ― Industrial Experience. The topic of this particular post is ‘Excessive Cost Reduction’.

It starts as follows.

FLAG #2 — EXCESSIVE COST REDUCTION

The discussion to do with production creep in the first part of this chapter stated that managers are often asked to achieve greater production using just existing resources. In fact, the situation is often worse than this; managers are often also asked to cut expenses at the same time as they are increasing production rates. The mantra for this philosophy is, “Do More with Less”. If the cost-cutting becomes excessive then a warning flag should be raised.

In his book Lessons from Longford (Hopkins 2000) states, “when we extend the causal network < for an accident > far enough, market forces and cost cutting pressures are almost invariably implicated”.

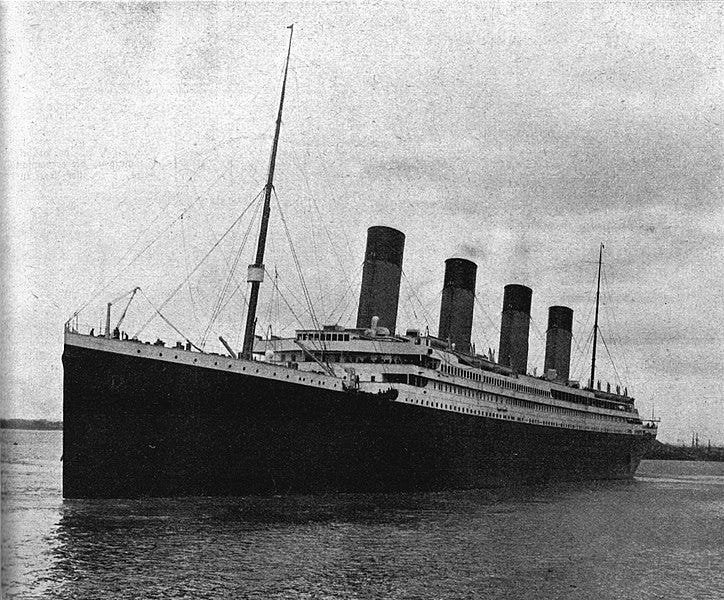

Why the Titanic Really Sank

The paper The Titanic Disaster: An Enduring Example of Money Management vs. Risk Management (Brander 1995) that was referenced in Chapter 1 discusses cost cutting pressures. The following is a quotation from that paper.

Most of the discussion of the accident revolves around specific problems. There was the lack of sufficient lifeboats (enough for at most 1200 on a ship carrying 2200). There was the steaming ahead at full-speed despite various warnings about the ice-field. There was the lack of binoculars for the lookout. There were the poor procedures with the new invention, the wireless (not all warnings sent to the ship reached the bridge, and a nearby ship, the operator abed, missed Titanic's SOS). Very recently, from recovered wreckage, "Popular Science" claimed the hull was particularly brittle even for the metallurgy of the time. (A claim now debunked.) Each has at one time or another been put forward as "THE reason the Titanic sank".

What gets far less comment is that most of the problems all came from a larger, systemic problem: the owners and operators of steamships had for five decades taken larger and larger risks to save money - risks to which they had methodically blinded themselves. The Titanic disaster suddenly ripped away the blindfolds and changed dozens of attitudes, practices, and standards almost literally overnight.

Of course, managers have always been under pressure to cut costs. However, for the last twenty years or so this pressure has become ever more relentless — largely due to global competition. In such an environment a manager may think on the following lines:

Three years ago, under pressure from head office, we downsized our engineering department from 20 to 15 professionals. The savings helped the plant meet its financial goals (and also improved my bonus). Head office was so pleased with the result that a year later we cut another five engineering professionals. Some of the nagging reliability problems we have had since then can probably be attributed to these cuts, but we did improve profitability once again, and I have to accept that our operation is hanging in there.

Maybe it was because of this success in cutting costs, senior management decided to re-locate four of the remaining ten professionals to head office (200 kilometers away) so as to reduce travel costs and office expenses. So now we are down to six on-site engineers from the 20 we had just three years ago.

I’m worried that we may be heading for a major accident because we have cut our technical support so drastically. Maybe I should raise a warning flag. However, I can’t be sure, so I’ll just have to trust to luck. After all, serious accidents happen only rarely, and I expect to be assigned to a new position within a year or two. Then these worries become someone else’s problem.

The current Table of Contents for the book is here.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Net Zero by 2050 to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.