The 300-Year Party: The Atmospheric Engine

This post is the second in a four-part series describing how we became so dependent on fossil fuels. The first post is The 300-Year Party: Peak Forests.

In the year 1712 a Baptist preacher named Thomas Newcomen developed a steam-powered engine for pumping water out of the mines in Cornwall, England. Newcomen’s engine was powered by coal, the über-commodity of the 19th century; it was coal that put the ‘Great’ in ‘Great Britain’.

Coal was not a new source of fuel; indeed, the smoke from coal fires was considered to be an environmental nuisance early in the Middle Ages. Coal had always been particularly useful for blacksmiths who needed a high temperature fire for their work. But the supply of coal was limited because their only source was either from surface seams, or from where it washed up on the beaches (sea coal). By the beginning of the 18th century these sources of were insufficient to meet the needs of an industrializing society. There was, however, plenty of coal underground. But, as we have already noted, the countries of northern Europe have a wet climate, which meant that they usually had a high water table. Hence the new coal mines often flooded. Therefore, some means of pumping the water out of the mines was needed.

To do this they needed two technological developments. First, they needed high-capacity pumps to remove the water from the mine; second, they needed engines to drive the pumps because humans or animals could not provide sufficient power. Hence, necessity being the mother of invention, the industrialists of that time invented the coal-powered steam engine.

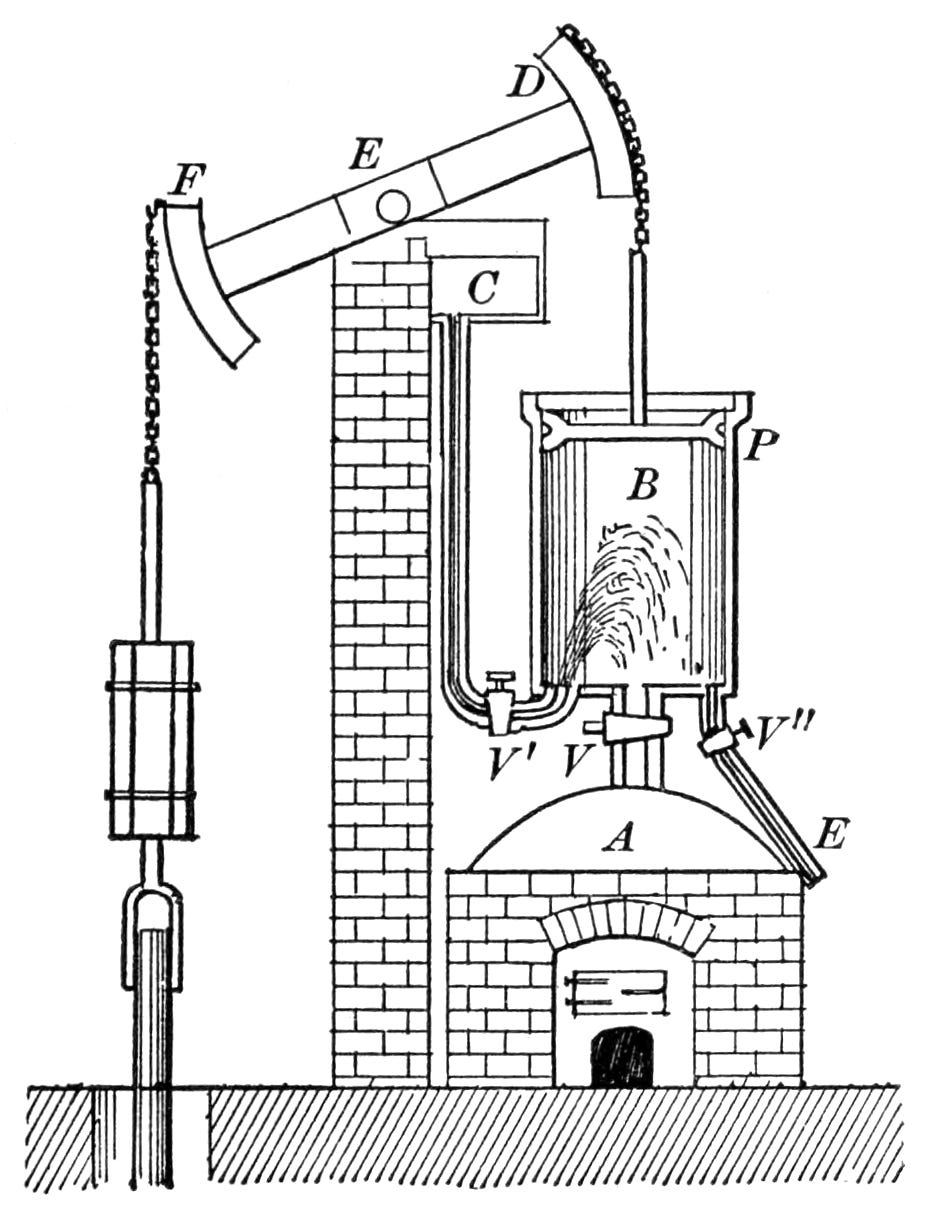

Newcomen’s engine was not, strictly speaking, a steam engine; it was actually an “atmospheric engine”. It worked by filling a cylinder with steam that drove the piston upwards. Cold water was then injected into the cylinder such that the steam was condensed. The piston in the cylinder was then driven downward by atmospheric pressure. This downward movement of the piston that was the power stroke.

Newcomen’s pump was abysmally inefficient because the entire system was cooled down in order to condense the steam in the cylinder, and then had to be re-heated, for the next stroke. But his machine did have one important feature shared by all good engineering innovations: it worked. In fact, it was so good that Newcomen even got his picture on a first-class postage stamp.

Newcomen’s engine was first used in the tin mines of Cornwall. But it was quickly adopted by the men running the new coal mines. And it did not take long for other inventors, men such as James Watt, to design and develop much more efficient machines.

Newcomen and those who followed him did not develop these early engines merely because it seemed like a good idea. Model steam engines such as the aelophile, an early form of a steam turbine, had been invented two thousand years earlier, but had never been commercialized. The aelophile was merely a toy — the people of that time did not perceive a need for a new source of energy, so they never bothered to develop this primitive steam turbine. The engineers of Newcomen’s time developed the industrial steam engine because they had to — they needed to respond to the predicament of what could be referred to as ‘Peak Forests’.