As little as 12 months ago the world’s business leaders and politicians were promoting ‘Net Zero by 2050’ ― NZ2050. Now those words are rarely heard. Why not?

The answer is painfully obvious ― it’s not going to happen. It never was a realistic goal. And our failure to even make even modest progress is embarrassing at best, and frightening at worst.

The NZ2050 goal came from COP21 ― the international meeting that was held in Paris in the year 2015. Since that time, almost ten years ago:

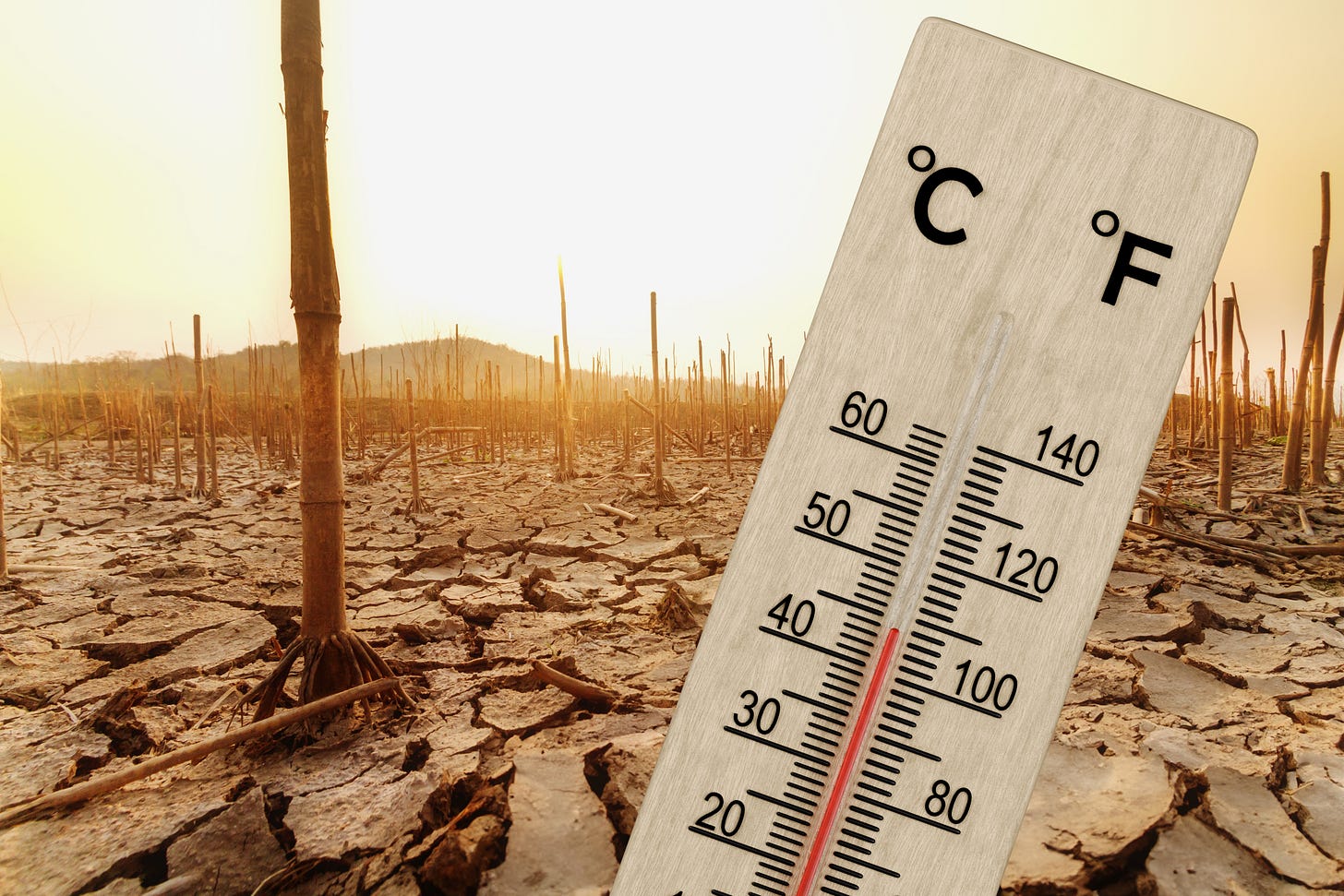

Greenhouse gas emissions have steadily increased,

The concentration of CO2 (carbon dioxide) in the atmosphere has risen steadily,

Each year sets a new record for high global temperatures,

Hurricanes, droughts and floods are increasing in frequency and severity,

Ice sheets and icebergs are melting at an ever-increasing rate,

Refugee crises are worse than ever,

and so on.

Why has the phrase NZ2050 been dropped so quickly and easily? Probably the core reason is as follows,

We cannot maintain infinite growth on a finite planet. Yet all of our business, financial and political goals depending on maintaining non-stop economic growth.

Here is what we wrote just a year ago.

Net Zero by 2050

The phrase ‘Net Zero by 2050’ has been adopted by many organizations. They have committed to zero emissions of greenhouse gases (principally carbon dioxide and methane) by the year 2050. (The word ‘Net’ allows them to take credit for actions they take to remove greenhouse gases, and so compensate for their emissions.)

Conferences of the Parties / The IPCC

The United Nations organizes an annual ‘Conference of the Parties’ (COPs) to address climate change challenges at the national and international level. COPs are attended by government leaders from around the world. The first COP was held in Berlin, Germany in March 1995. The 21st ― and maybe the most important ― COP was held in Paris in the year 2015. National leaders from all over the world created a unified policy and a legally binding treaty known as the Paris Agreement. It called for countries to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C the pre-industrial baseline, and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C by the year 2020.

The mood at COP21 was optimistic. Nevertheless, the signatories to the Agreement recognized that they had set themselves very challenging goals so they asked the IPCC (the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) to determine what actions would be needed to keep the temperature increase below 1.5°C by the year 2030.

The IPCC is a United Nations body that was created in the year 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme. Its role is to provide policymakers with regular scientific assessments on the current state of knowledge about climate change. The IPCC does not conduct its own research; its reports are written by teams of unpaid volunteers based on information compiled from thousands of peer-reviewed scientific papers.

The quality and conservatism of the IPCC’s work makes it an authoritative source of information to do with climate change. Nevertheless, the organization does have its critics. For example, many environmentalists fault it for being overly cautious by downplaying the seriousness of climate change and its impacts. (If this criticism is valid then those who use the IPCC analyses and projections cannot be accused of alarmism.)

The work of the IPCC is also criticized because it focuses just on climate change — in the past it has failed to consider issues such as the depletion of oil reserves, population growth and the loss of biodiversity. In response to this criticism the organization is starting to integrate other parameters into its analyses. For example, the Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability report states,

This report recognizes the interdependence of climate, ecosystems and biodiversity, and human societies and integrates knowledge more strongly across the natural, ecological, social and economic sciences than earlier IPCC assessments.

In spite of the optimism generated at COP21 many critics tried to inject a dose of realism. For example, in his 2019 book The Uninhabitable Earth, David Wallace-Wells says,

At Paris in 2015 world leaders agreed to ‘pursue efforts’ to keep the rise in global temperatures below 1.5°C. After signing the agreement with great fanfare, they returned home and quietly continued with business as usual: growing the economy, building more fossil-fuelled power plants, expanding road networks for ever more oil-guzzling cars and SUVs, and drilling or fracking over larger and larger area. Never mind all the warm words at the UN meetings, all the tearful waffle about ‘future generations looking us in the eyes’, the pats on the head for teenage climate activists and the like. It is the hard stuff in the real world that matters: tarmac, pipelines, refineries, gas turbines, petrol engines and coal boilers. This is where the carbon hits the atmosphere. This is where the future is decided.

The Global 1.5°C Report

In response to the request from the signatories to the Paris Agreement, the IPCC published what is probably its most important report, Global Warming of 1.5°C. (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018). That report contains the following remarkable sentence.

In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range).

< my emphasis >

This critically important sentence is at the 24th reading grade level; in other words, it is unreadable. Of it, the journal Bloomberg Green said,

Like most statements the IPCC sets down, the most important sentence ever written is just terrible—clunky and jargon-filled. What it says, in English, is this: By 2030 the world needs to cut its carbon-dioxide pollution by 45%, and by midcentury reach “net-zero” emissions, meaning that any CO₂ still emitted would have to be drawn down in some way . . .

. . . it may turn out to be the grammatical unit that saved the world. If not, it'll be remembered as the last, best warning we ignored before it was too late.

In spite of the fact that the IPCC report is difficult to read, the phrase ‘net zero around 2050’ caught on. The words ‘Zero’ or ‘2050’ are pithy and memorable, and the phrase itself contains plenty of zeroes, thus providing an easy-to-understand and memorize target.

The year 2050 is, of course, an arbitrary deadline. Mother Nature/Gaia is going to do what she wants to do both before and after the year 2050. But human beings need easily-understood goals.