Limits and Beyond: No More Growth

A Review of Chapter 2

The book Limits and Beyond, edited by Ugo Bardi and Carlos Alwarez Pereira, provides a 50th anniversary review of the seminal report Limits to Growth (LtG). The following is from the back cover of the book.

50 years ago the Club of Rome commissioned a report: Limits to Growth. They told us that, on our current path, we are heading for collapse in the first half of the 21st century. This book, published in the year 2022, reviews what has happened in the intervening time period. It asks three basic questions:

Were their models right?

Why was there such a backlash?

What did the world do about it?

Our review of the first chapter drew two major conclusions.

There is a “yawning communications gap” between the scientists who developed the LtG model and the public and policy makers. This failure of communication contrasts with the way in which many Evangelical Christians believe in ‘The Rapture’. Yet both LtG and ‘The Rapture’ provide a vision for TEOTWAWKI (The End of the World as We Know It). Why did scientific communication fail, while religious communication flourished?

Reports such as LtG tend to have a threatening tone. They say that if we do not take action quickly then we are going to be in serious trouble. Yet people generally respond better to a positive message. Had the report described the opportunities that a world without growth offers it may have had a better reception.

The second chapter is written by one of the original LtG authors: Jorgen Randers. The chapter’s title is “What did The Limits to Growth really say?”

Decoupling Economic and Physical Growth

He makes the point that LtG was not a prediction of the future. It was, in fact, “a scenario analysis of 12 possible futures of the period 1972 to 2100”, and, “. . . delays in global decision making would cause the human economy to overshoot planetary limits before the growth in the human ecological footprint slowed.”

In other words, either we manage decline in a controlled manner (which we have not done) or else collapse happens to us, whether we like it or not. One option that is not open to us to maintain Business as Usual, i.e., a continuation of material growth that simultaneously expands our ecological impact. In other words, the report did not predict the end of growth — it merely predicted, as its title suggests, limits to growth.

How economic growth could continue without simultaneous physical growth the report did not say — it did not show how to decouple these two types of growth. The experience of the last 50 years shows that the two have remained linked to one another inextricably. It appears as if decoupling is not possible. (At least, there has been no serious attempt to do so.)

The Test of Time

Randers asks, “Has the message of LtG stood the test of time?” His response is that “the real world has evolved as foreseen in LtG”. In other words, LtG has withstood the test of time. The report provides 12 different scenarios, they are all similar to one another up to about the year 2020. Events of the past 50 years have followed what these scenarios forecast.

To summarize,

Economic growth and the use of physical resources are tightly linked. Decoupling does not appear to be a possibility.

The scenarios in LtG up to our time the present day have turned out to be reasonably accurate.

We are now in overshoot. Managed decline has not happened; collapse is in our future.

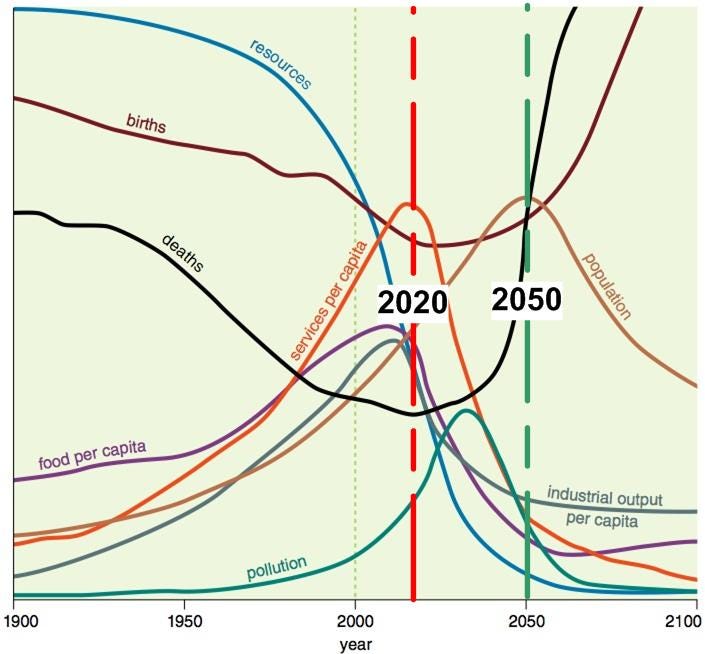

Given this background, it is useful at this point to show one of the scenarios that were presented in LtG. (I have added the date overlays.)

The chart makes for grim reading. It shows that, starting about now,

The world’s population increases for the next 30 years (which is why some of the per capita numbers are so unfavorable),

Services per capita drop precipitously,

Industrial output per capita drops almost as quickly,

Available resources plunge,

Pollution, which includes greenhouse gas emissions, climbs steeply, but then declines, presumably as a consequence of the rapid decline in industrial output.

Food per capita also drops sharply — a phenomenon that is one of increasing concern this year.

It is no surprise that a colleague of mine who is very familiar with climate change issues prefers not to look at this chart.

Technological Fix

A common response to results such as those shown in the chart is that technology will provide “save us”. Randers says that, “many thoughtful observers . . . believe that technology will be able to remove planetary limits faster than the rate at which we approach them.”

The report does not predict if, “investments in electrification and renewable energy will take place at sufficient pace to halt global warming.” In fact, it seems unlikely that such a transition will happen in the short amount of time available. (Once more, we could have managed such a transition had we acted with resolve 50 years ago — but we didn’t.) We now understand that no source of “green” energy has the unique combination of properties provided by fossil fuels, particularly crude oil. Moreover, the transition to new energy sources will require an immense use of fossil fuel energy. Technology may provide some useful responses, but it is not “the answer”.

Conclusion

In the ‘Final Reflection’ that concludes Chapter 2, Randers points out that LtG was published when “human belief in the power of technology was at an all-time high”. That belief is not what it was fifty years ago.

Moreover, there seems to be no way to establish economic growth while not increasing our ecological footprint. Hence, this chapter leads to the well-worn refrain that we should have taken action, but we didn’t. But we have left it much too late to implement managed decline (even if there were any serious interest in doing so, which there isn’t). Therefore some form of induced collapse is in our future.

Essentially, the message of this chapter is the same as it was for Chapter 1 — it is one of failed communication. We never gained the Name of Action.