In the late 1990s a processing plant in the southern United States suffered a severe explosion. Although no one died, some workers were seriously injured, and the economic loss was calamitous. Following the disaster the plant manager wrote an unpublished paper called Warning Flags over Your Organization. In this paper, which he presented to his management team, he attempted to explain how this facility, whose normal safety metrics (such as lost-time accidents and recordables) were quite good, could have reached a point where it quite literally blew up.

The subtitle of the paper was ‘How Lucky Are You Feeling Today?’ The author recognized that most facility managers elect to take risks, and, that most of the time, there are no serious consequences resulting from such decisions. Moreover, their tenure in their current job is likely to be relatively short, so they can hope to run out the clock — any problems can be addressed by the next manager. However, in the case of this manager the good luck ran out on his watch. His paper spoke to those issues that ‘everyone knows about, but that no one is willing to address’.

The manager started his paper by noting that virtually all process facilities in the United States fly three flags at the front gate: the flag of the United States, the flag of the State in which the facility is located, and the company flag. He suggested that if a facility has crossed a safety threshold then a fourth flag — analogous to a storm warning flag — should be flown. Of course, the idea of flying a warning flag in this manner was suggested tongue-in-cheek, but the idea of recognizing that an unsafe zone has been entered and that a storm threatens is a vital component of any company’s culture.

The basic idea behind warning flag concept is that, as an organization is stretched further and further sudden and catastrophic failure is more likely to occur. An analogy is with a rubber band, which, as it is stretched further and further, will eventually reach a point where it suddenly snaps; it fails not gradually, but suddenly and totally. In other words, health, safety and environmental problems do not necessarily provide early indications of potentially serious problems; the first signs of trouble could be a sudden and massive failure.

The following six indicators or warning flags can help management determine if they have crossed a safety threshold.

Unrealistic stretch goals;

Excessive cost reduction;

Belief that “It Cannot Happen Here”;

Over-confidence based on rule compliance;

Departmentalized information flow; and

Ineffective audit processes.

In this post we consider the second of these topics: Excessive Cost Reduction.

The discussion in the first post — Unrealistic stretch goals — to do with production creep stated that managers are often asked to achieve greater production using just existing resources. In fact, the situation is often worse than this; managers are often also asked to cut expenses at the same time as they are increasing production rates. The mantra for this philosophy is, “Do More with Less”. If the cost-cutting becomes excessive, then a warning flag should be raised.

The book Lessons from Longford (Hopkins 2000) states, “when we extend the causal network < for an accident > far enough, market forces and cost cutting pressures are almost invariably implicated”.

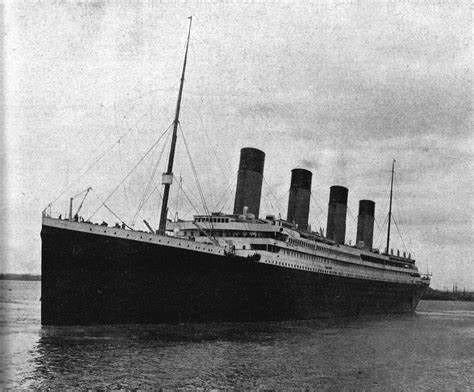

The paper The Titanic Disaster: An Enduring Example of Money Management vs. Risk Management (Brander 1995) that was referenced in Chapter 1 discusses cost cutting pressures. The following is a quotation from that paper.

Most of the discussion of the accident revolves around specific problems. There was the lack of sufficient lifeboats (enough for at most 1200 on a ship carrying 2200). There was the steaming ahead at full-speed despite various warnings about the ice-field. There was the lack of binoculars for the lookout. There were the poor procedures with the new invention, the wireless (not all warnings sent to the ship reached the bridge, and a nearby ship, the operator abed, missed Titanic's SOS). Very recently, from recovered wreckage, "Popular Science" claimed the hull was particularly brittle even for the metallurgy of the time. (A claim now debunked.) Each has at one time or another been put forward as "THE reason the Titanic sank".

What gets far less comment is that most of the problems all came from a larger, systemic problem: the owners and operators of steamships had for five decades taken larger and larger risks to save money - risks to which they had methodically blinded themselves. The Titanic disaster suddenly ripped away the blindfolds and changed dozens of attitudes, practices, and standards almost literally overnight.

Of course, managers have always been under pressure to cut costs. However, for the last twenty years or so this pressure has become ever more relentless — largely due to global competition. In such an environment a manager may think on the following lines:

Three years ago, under pressure from head office, we downsized our engineering department from 20 to 15 professionals. The savings helped the plant meet its financial goals (and also improved my bonus). Head office was so pleased with the result that a year later we cut another five engineering professionals. Some of the nagging reliability problems we have had since then can probably be attributed to these cuts, but we did improve profitability once again, and I have to accept that our operation is hanging in there.

Maybe it was because of this success in cutting costs, senior management decided to re-locate four of the remaining ten professionals to head office (200 kilometers away) so as to reduce travel costs and office expenses. So now we are down to six on-site engineers from the 20 we had just three years ago.

I’m worried that we may be heading for a major accident because we have cut our technical support so drastically. Maybe I should raise a warning flag. However, I can’t be sure, so I’ll just have to trust to luck. After all, serious accidents happen only rarely, and I expect to be assigned to a new position within a year or two. Then these worries become someone else’s problem.

Another quotation of the same type as Brander’s comments to do with the Titanic is shown below. It is taken from an unattributed slide show presentation following the sinking of a 33,000 tonne offshore platform (P36 in Brazil) — what was then the world’s largest floating production platform — in the year 2001. The quotation purports to be taken from a memo written by a manager on the project during the design and construction phases of the project.

< Our company > has established new global benchmarks for the generation of exceptional shareholder wealth through an aggressive and innovative programme of cost cutting on its new facility. Conventional constraints have been successfully challenged and replaced with new paradigms appropriate to the globalised corporate market place. Through an integrated network of facilitated workshops, the project successfully rejected the established constricting and negative influences of prescriptive engineering, onerous quality requirements, and outdated concepts of inspection and client control. Elimination of these unnecessary straitjackets has empowered the project's suppliers and contractors to propose highly economical solutions, with the win-win bonus of enhanced profitability margins for themselves. The platform shows the shape of things to come.

Examples of cost-cutting measures that can lead to problems include the following:

Reduction of “non-essentials”;

Reductions in the size of the work force;

The “Big Crew Change”

Flattened organizations;

Aging infrastructure;

Out-sourcing;

Not enough time for detailed work;

Project cutbacks; and

Organizational spread.

Reduction of “Non-Essentials”

When managers want to cut costs they first look for supposedly “non-essential” activities or resources, such as training or excessive inventory of spare parts in the warehouse. Reducing expenditures on such activities and resources certainly leads to short-term cost reductions. However, over a longer period of time these cuts can create unsafe conditions. In Lessons from Longford Hopkins notes that cuts in the maintenance budget played a major role in that disaster.

A careful analysis of the findings from a facility’s incident investigations can help determine if cost-cutting measures may have gone too far. For example, if many incidents result from people not having sufficient training, then maybe the Training Department was “slimmed down” too far. Alternatively, if those incidents result from failed equipment items then the Maintenance Department needs to be provided with more resources.

Reductions in Work Force

In recent decades companies have been relentless in their drive to reduce head count. The pressures to do so have often resulted from mergers and acquisitions where the justification for the merger was that overlapping and duplicated functions could be eliminated, thus resulting in the elimination of “unnecessary” jobs. However, such cuts may represent a false economy; indeed merging two organizations may actually require a temporary increase in the number of service personnel so that the two different systems and cultures can be integrated successfully.

One particularly troublesome issue to do with work force reductions is that, when cuts are made, it is often the personnel with more experience who leave. Such people, being older, are more likely to be qualified for early retirement or “the package”. Also, their departure leads to a greater reduction in costs because they are paid more than the younger employees. Unfortunately, this means that the newer people have fewer gray-haired mentors to monitor their actions and decisions. This loss of experience problem is not new - indeed it is the theme of Trevor Kletz’s book, Lessons from Disaster - How Organizations Have No Memory and Accidents Recur (Kletz 1993).

Staff reductions have been particularly noticeable in corporate and engineering departments because many of the people who work in those departments are not perceived as being critical to the attainment of short-term production goals. Therefore, it is often felt that they can be released (or not replaced when they retire). If their expertise is required, it is argued, then experts from outside companies can be brought in on a contract basis. In fact, managers may choose not to bring in anyone at all. They may simply ask their remaining personnel to carry out a larger number of tasks. Such a strategy creates three difficulties.

The engineers that remain have more work to do in the same amount of time than they had in the past. Therefore, no matter how dedicated they may be, it is likely that their work will not be as thorough as it would have been in the past when more time was allowed to study specific technical issues.

There will be fewer subject matter experts to help identify and correct problems. If the company expert to do with pressure relief valves, say, retires and is not replaced, then problems with the design and operation of relief valves may not even be identified.

Even if outside experts or retirees are brought in, they will not be au courant with what is going on at the facility, so it is less likely that they will be able to offer immediate help. There is some company knowledge that cannot be brought in off the street. If a person has worked at a company for many years, particularly in a specialist department, and he leaves without having trained a replacement, there is almost certain to be a loss of “corporate memory”. People brought in from the outside may be very knowledgeable, but they cannot possibly know all of the history and background as to why things are the way they are at this particular location.

The “Big Crew Change”

A phrase sometimes used in the petroleum industry to describe the loss of experienced personnel is “Big Crew Change” (Gell 2008) , also referred to as the “silver tsunami”. The phrase is mainly used with regard to the large number of baby-boomer generation engineers and technical experts who will be retiring after the year 2010. These experienced personnel are not being replaced by sufficient younger people with comparable technical skills and experience. For example, it has been reported that,

Between 1983 and 2002, the number of U.S. petroleum engineers declined from 33,000 to 18,000 . . .

In other areas of plant operations, the loss of personnel is compensated for by using increasingly powerful computer systems. For example, a DCS (Distributed Control System) can carry out many of the functions previously performed by several operators. Similarly, sophisticated design software lets one engineer carry out calculations that previously had to be done by a team. Yet there remain certain actions that have to be carried out by people; the loss of skilled personnel in these situations represents a true loss.

Flattened Organizations

Gaps between the layers of management have grown as a result of programs that “flatten the organization”. Consequently the gaps between the layers of supervision and management have increased. Relatively junior and inexperienced employees are called on to make decisions without being able to tap into the guidance and assistance of more experienced personnel. Moreover, newer employees will have fewer opportunities to learn from their more experienced predecessors during the normal course of their work.

Another concern is that the number of experienced people in many organizations has been reduced, Hence, many process changes that were previously handled quickly and effectively on a semi-formal basis by experienced personnel who knew each other very well, and who also had an intimate knowledge of the processes for which they were responsible now must be handled in a more formal manner.

Aging Infrastructure

Not only is the workforce aging, so is the equipment itself. The manager of a large U.S. oil refinery dating from the 1920s recently said of his facility that, “The steel is tired”. He was concerned that an accident could occur because so much of the equipment was old and worn out and that it was not being replaced or upgraded quickly enough. Another manager, this time at an old petrochemical plant, said, “My plant is old but the engineers are young”. He did not intend his phrase as a compliment. He was worried about the problems caused by old equipment and the fact that his technical staff lacked the knowledge and experience to address those problems.

Out-Sourcing

One way in which staff reductions can be made, while keeping the organization functioning, is to out-source work to outside companies and personnel. If the work is truly one-off, such as the engineering and installation of a new piece of equipment, then the use of an outside company will usually be the best choice. However, if the work being out-sourced is a core function then this strategy can create difficulties. No outsider, no matter how experienced and talented, can know all aspects of an operation in the way that a long-term employee can.

For example, on one plant a particular compressor started to vibrate slightly. The long-term employees knew that this vibration was the precursor to a more serious problem, and that immediate corrective action was needed. However, these employees had been replaced with outside contract workers. The new workers did not recognize the seriousness of the vibration, hence they did not take corrective action quickly enough, and a serious leak of process fluids occurred.

The loss of experienced personnel also reduces the chance of developing long-term solutions to operational or maintenance issues. A contract worker is less likely to care about such long-term issues, and so is less likely to make suggestions and contributions. Yet the involvement of all employees is crucial to the success of a process safety program.

Not Enough Time for Detailed Work

One consequence of the relentless reductions in the work force is that people become so busy that they do not have enough time for detailed work. In particular, they do not have time to check their work, or the work of their colleagues. Hence a greater chance that errors will slip through exists.

In engineering and design companies, the lack of resources can lead to calculations not being properly checked. In the case of operating facilities, the lack of time for detailed work may lead to operating instructions being written without being checked or work permits being issued in haste.

Project Cutbacks

It is an unusual project that does not run into scheduling and/or budget problems. Such problems inevitably create pressure to take short-cuts or to eliminate some equipment items so as to get the project back on schedule thereby increasing the chance of a PSM short cut. The Management of Change and Operational Readiness programs should help ensure that such actions do not create an unacceptable safety problem.

Organizational Spread

One feature of the increased globalization of commerce is that an increasing amount of project work is spread around the world. This is done to reduce costs and to exploit the availability of skilled personnel.

Spreading work around the world means that companies have to rely heavily on their formal decision-making processes; there is less opportunity for person-to-person interaction. Yet it is just such interactions that are invaluable in risk management work, particularly with regard to the identification and assessment of hazards. The more the organization is spread, the greater the belief that process is all and that no special, subjective skills are required.