This morning I read a sad article in the January 2025 edition of Hydrocarbon Processing (HP). The article tells us that the company INEOS is closing last remaining synthetic ethanol plant in the UK. (The plant is located in Grangemouth, Scotland.)

The article starts as follows.

High energy prices and high carbon taxes have forced the closure of this strategic UK asset.

The UK, which used to be a major force in chemicals, employing a large and highly skilled workforce, has seen the closure of ten large chemical complexes in the last five years alone and, in complete contrast to the USA, has not had one new chemical plant built for a generation.

Energy prices have doubled in the UK in the last five years and now stand five times higher than those in the USA. The UK cannot compete with such a huge disadvantage.

This article hit me personally since I started my chemical engineering career in the chemical industry in the north of England.

If the problem were confined to UK energy policy then we could move on. But the article has lessons for us all.

Coal

It was coal that put the ‘Great’ in ‘Great Britain’.

Britain was the first country to industrialize, largely because it had access to large supplies of coal and running water, particularly in the north of England and southern Wales. It was the energy provided by coal that literally fueled the Industrial Revolution.

But, by as early as 1900, coal supplies started to dwindle. (Or more specifically, the EROEI ― Energy Returned on Energy Invested ― for coal declined.) Industrial leadership gradually passed to Germany and the United States.

By the 1970s the decline of the coal industry had led to considerable social unrest. Employment in that industry had fallen from over 700,000 to under 300,000 between the 1950s and 1970s. One consequence of this decline was the angry miner’s strike of 1972.

Although that strike was a victory for the miners in the short term, it could not avert the long-term decline in coal mining. (A theme of the posts at this site is that when the ‘laws’ of economics clash with the laws of physics and thermodynamics, then it is physics that wins.)

Oil

In the 1970s the UK received a reprieve: North Sea Oil. That abundant new energy source provided the energy that is foundational to all industrial societies. But, just like coal, the production of oil declined from its peak of around 6 million barrels per day in 1999 to just over 1 million barrels per day now. (The Financial Times projections are that production will be close to zero by the year 2040.)

It is the decline in available energy, first from coal and then from oil, that explains the statement in the Hydrocarbon Processing article,

High energy prices and high carbon taxes have forced the closure of this strategic UK asset.

United States

The HP article suggests that the United States is in a much better place because,

Energy prices have doubled in the UK in the last five years and now stand five times higher than those in the USA.

Not so fast.

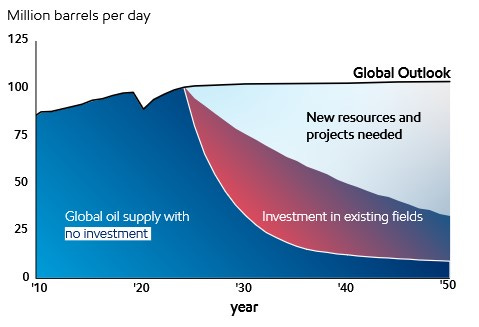

Let us revisit the ExxonMobil report from August 2024. As I have said in previous posts, such as An Astonishing Projection, I regard the above chart from the XOM report as being more important than the recent election results in the United States. If the XOM projections turn out to be even close to correct, then the United States will face the same problems as the UK just a few years from now regardless of the nation’s energy policies. It bears repeating,

The laws of physics and thermodynamics will always beat the ‘laws’ of economics.

The Cost of Net Zero

The HP article attributes the loss of UK industry not only to high energy prices but also high carbon taxes.

In defense of UK government policy, the government has recognized the challenge that declining coal and production present, and so has invested heavily in alternative energy sources, particularly offshore wind. But the investment funds have to come from somewhere, and that ‘somewhere’ is ever-increasing taxes on the oil industry. Hence INEOS had to shut down the Grangemouth facility.

This decision to invest in new sources of energy is commendable, and deserves our full support. However ― back to physics and thermodynamics ― wind (and solar) do not provide anything like the energy density of coal, oil and natural gas. Moreover, the energy that they supply is very intermittent, so there is still a need to build backup power plants that use natural gas or coal.

Conclusions

As I have said in previous posts, I started this substack with the intention of analyzing new sources of ‘green’ energy. Which of them would allow us to achieve ‘Net Zero’ emissions in the shortest time and with the least waste of effort. The high point of this way of thinking was the Paris Agreement that came out of COP21 in the year 2015.

It soon became apparent that people and governments around the world were not willing to make the commitments and sacrifices that were called for. Since 2015 our consumption of fossil fuels has steadily increased, as have our greenhouse gas emissions.

This discouraging conclusion does not mean that we give up looking for alternative energy sources. But it does mean that we recognize that we cannot necessarily have our environmental cake and eat it.

This review of the INEOS decision regarding its Grangemouth facility reinforces this way of thinking.