ALARP and Acceptable Risk

Fundamentally risk is subjective; it is not possible to define what level of risk is acceptable dispassionately and objectively. Any two risk scenarios are inherently different from one another due to people’s inherent understanding and acceptance of different types of risk, their emotions, memories, hopes and fears.

Factors that affect risk perception include the following:

Degree of control.

Familiarity with the hazard.

Direct benefit.

Personal impact,

Natural vs. man-made risks,

Recency of events,

Effects of the consequence term, and

Comprehension time.

In spite of these difficulties, it is still necessary to have a clear understanding as to what levels of risk are acceptable. After all, if a facility operates for long enough, it is certain - statistically speaking - that there will be an accident. Therefore, process safety professionals need guidance as to what level of "acceptable safety" is required. This is tricky. Regulatory agencies in particular will never place a numerical value on human life and suffering because any number that they propose would inevitably generate controversy. Yet working targets have to be provided, otherwise the facility personnel do not know what they are shooting for. Nor can a regulatory body, a professional society or the author of a book such as this can provide an objective value for risk.

Individuals and organizations are constantly gauging the level of risk that they face in their personal and work lives, and then acting on their assessment of that risk. For example, at a personal level, an individual has to make a judgment as to whether it is safe or not to cross a busy road. And there is the further complication of the subjectivity of risk. Someone who is strongly opposed to having a chemical plant near their home may happily choose to go bungee jumping at weekends.

In an industrial context managers make risk-based decisions regarding issues such as whether to shut down an equipment item for maintenance or to keep it running for another week. Other risk-based decisions made by managers are whether or not an operator needs additional training, whether to install an additional safety shower in a hazardous area, and whether a full Hazard and Operability Analysis (HAZOP) is needed to review a proposed change. Engineering standards, and other professional documents, can provide guidance. But, at the end of the day, the manager has a risk-based decision to make. That decision implies that some estimate of "acceptable risk" has been made.

One company provided the criteria shown for its design personnel.

Fatalities per year (employees and contractors) Intolerable risk >5 x 10-4

High risk <5 x 10-4 and >1 x 10-6

Broadly tolerable risk <1 x 10-6

Their instructions were that risk must never be in the 'intolerable' range. High risk scenarios are "tolerable", but every effort must be made to reduce the risk level, i.e.,to the "broadly tolerable" level.

Perfection as a Slogan

Although perfect safety may not be theoretically achievable, many companies will use slogans such as Accidents Big or Small, Avoid them All. The idea behind such slogans is that the organization should strive for perfect safety, even though it is technically not achievable.

Whether such slogans have a positive effect is debatable. Many people view them as being simplistic and not reflecting the real world of process safety. They seem to over-simplify a discipline that requires dedication, hard work, education, imagination and a substantial investment. For example, a large sign at the front gate of a facility showing the number of days since a lost-time injury is not likely to change the behavior of the workers at that facility. Indeed, it may encourage them to cover up events that really should have been reported. Or to be cynical about the reporting system.

As Low as Reasonably Practical - ALARP

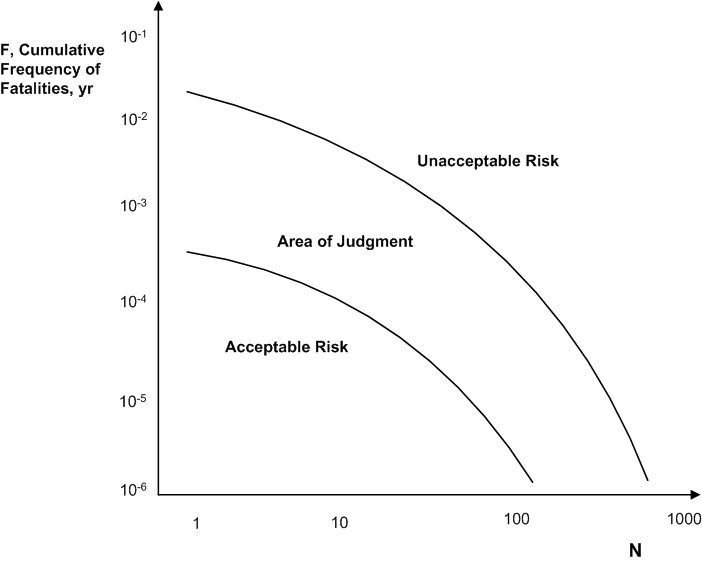

Some risk analysts use the term 'As Low as Reasonably Practical (ALARP)' for setting a value for acceptable risk. The basic idea behind this concept is that risk should be reduced to a level that is as low as possible without requiring "excessive" investment. Boundaries of risk that are definitely acceptable or definitely not acceptable are established as shown in the chart, which is an FN curve family. Between those boundaries, a balance between risk and benefit must be established. If a facility proposes to take a high level of risk, then the resulting benefit must be very high.

Risk matrices can be used to set the boundaries of acceptable and unacceptable risk. The middle squares in such a matrix represent the risk levels that are marginally acceptable.

One panel has developed the following guidance for determining the meaning of the term As Low as Reasonably Practical.

Use of best available technology capable of being installed, operated and maintained in the work environment by the people prepared to work in that environment;

Use of the best operations and maintenance management systems relevant to safety;

Maintenance of the equipment and management systems to a high standard;

Exposure of employees to a low level of risk.

The fundamental difficulty with the concept of ALARP is that the term is inherently circular and self-referential. For example, the phrase "best available technology" used in the list above can be defined as that level of technology which reduces risk to an acceptable level - in other words to the ALARP level. Terms such as "best operations" and "high standard" are equally question-begging.

Another difficulty with the use of ALARP is that the term is defined by those who will not be exposed to the risk, i.e., the managers, consultants and engineers who work safely in offices located a long way from the facility being analyzed. Were the workers at the site be allowed to define ALARP it is more than likely that they would come up with a much lower value.

Realistically, it has to be concluded that the term ALARP really does not provide much help to risk management professionals and facility managers in defining what levels of risk are acceptable. It may be for this reason that the United Kingdom HSE (Health and Safety Executive) chose in the year 2006 to minimize its emphasis to do with ALARP requirements from the Safety Case Regime for offshore facilities. Other major companies have also elected to move away from ALARP toward a continuous risk reduction model (Broadribb 2008).

One of the challenges to do with process safety management (PSM) is circular reasoning or logic. Many of the PSM elements can become self-referential. Process hazards analyses can illustrate this conundrum with discussions on the following lines.

Could high temperature in this vessel lead to a serious incident?

What is high temperature?

It’s that temperature that could cause a serious incident.

Similar difficulties can be seen when deciding on how to manage a proposed change to the facility. This time the question/answer sequence can go as follows.

Does this proposed change require implementation of the Management of Change (MOC) program?

We don’t know — we will have to run it through the MOC system to find out.

The same conundrum arises when using the concept of ALARP: As Low As Reasonably Practical Risk. What is meant by the word “reasonable”?

For example, a mechanical engineer and a process safety professional may be discussing the use of a new material of construction for a group of pressure vessels and their associated piping. Can they justify the cost and time delay that would be involved in making a change to the new material? The catch is that such a discussion will be fundamentally subjective — what is “reasonable” to one person may be “unreasonable” to another. There is no right or wrong answer — merely different opinions. The process safety professional may feel that it is “reasonable” to use the new material; after all, it is widely used by other companies. The engineer, on the other hand, may express concerns to do with funding and the time needed to install the new equipment and piping.

Similar concerns can be expressed with regard to the word ‘Practical’. In our example, the mechanical engineer may state that it is not practical to use the new material; the company has no experience of its use, so extensive training would be needed by those working in the construction and maintenance departments.

There is no definitive answer to the difficulties just raised. Risk is fundamentally a subjective matter. All that can be said is that, wherever possible, quantitative limits and goals need to be defined.

De Minimis Risk

The notion of de minimis risk is similar to that of ALARP. A risk threshold is deemed to exist for all activities. Any activity whose risk falls below that threshold value can be ignored - no action needs to be taken to manage this de minimis risk. The term is borrowed from common law, where it is used in the expression of the doctrine de minimis non curat lex, or, "the law does not concern itself with trifles". In other words, there is no need to worry about low risk situations. Once more, however, an inherent circularity becomes apparent: for a risk to be de minimis it must be 'low', but no prescriptive guidance as to the meaning of the word 'low' is provided.

Citations / Case Law

Citations from regulatory agencies provide some measure for acceptable risk. For example, if an agency fines a company say $50,000 following a fatal accident, then it could be argued that the agency has set $50,000 as being the value of a human life. (Naturally, the agency's authority over what level of fines to set is constrained by many legal, political and precedent boundaries outside their control, so the above line of reasoning provides only limited guidance at best.) Even if the magnitude of the penalties is ignored, an agency's investigative and citation record serve to show which issues are of the greatest concern to it and to the community at large.

RAGAGEP

With regard to acceptable risk in the context of engineering design, a term that is sometimes used is 'Recognized and Generally Accepted Good Engineering Practice' (RAGAGEP). This topic has been included in the proposed updates to OSHA’s process safety standard. Further information is provided at:

Update to OSHA’s Process Safety Management Regulation. Part 12: Definition of RAGAGEP, and

Update to OSHA's Process Management Regulation. Part 15: Updates to RAGAGEP

Indexing Methods

Some companies and industries use indexing methods to evaluate acceptable risk. A facility receives positive and negative scores for design, environmental and operating factors. For example, a pipeline would receive positive points if it was in a remote location or if the fluid inside the pipe was not toxic or flammable (Muhlbauer 2003). Negative points are assigned if the pipeline was corroded or if the operators had not had sufficient training. The overall score is then compared to a target value (the acceptable risk level) in order to determine whether the operation, in its current mode, is safe or not.

Although indexing systems are very useful, particularly for comparing alternatives, it has to be recognized that, as with ALARP, a fundamental circularity exists. Not only has an arbitrary value for the target value to be assigned, but the ranking system itself is built on judgment and experience, therefore it is basically subjective. The biggest benefit of such systems, as with so many other risk-ranking exercises, is in comparing options. The focus is on relative risk, not on trying to determine absolute values for risk and for threshold values.