A Failure of Expertise

As we all know, in the last few days the internet has been full of articles on how the government of the United States has chosen to dismantle its economy, and leave the world stage. Many of those articles are written by intelligent, highly educated people who have a sophisticated grasp of how the world works. However, these writers generally analyze recent events in the context of standard economics. They assume that the current crisis can be resolved through the use of conventional tools, such as changing interest rates or the creation of new free trade blocks.

Yet virtually none of these experts recognize that the physical world around them is changing ― and not for the better. These changes ― the collective Age of Limits ― include climate, resource depletion, biosphere destruction and loss of fresh water aquifers/top soil.

Three examples of how these limits are being ignored by the financial writers come to mind.

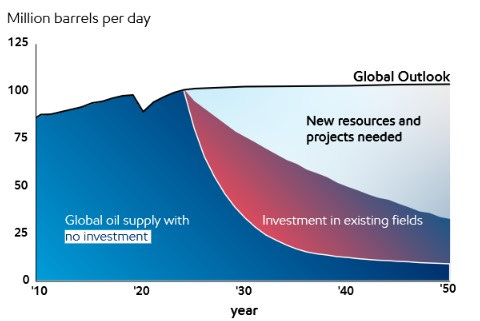

The first example is the projected drastic decline in oil supplies, as discussed in our post A Truly Extraordinary ExxonMobil Report. That report, written by the world’s largest non-government oil company, states that Oil supplies will plummet around the year 2026.

Why does this matter? Well, many of our financial experts are talking about creating a new free trade zone that will include Canada, Europe and the UK, but that will exclude the United States. The creation of such a zone assumes that raw materials and finished products can be moved around the planet as they are now. But, if oil supplies are both much more expensive and more limited, then a new free trade zone may not be physically realistic. There will be insufficient bunker fuel and aviation fuel, at least at anything close to current prices, to sustain a new free trade zone.

The second example is to do with climate change. As we experience simultaneous heat waves, floods and droughts around the world, global food production systems will be stressed, possibly to the point of regional collapse. This will lead to mass migration (from hotter to cooler areas) and a focus on growing food, rather than the manufacture of consumer goods. Globalization will revert to localization.

The third example concerns the concept of endless economic growth. Virtually all government leaders and financial experts assume that infinite growth on a finite planet can continue indefinitely. It is taken for granted that such growth can be brought about if we merely twiddle the right financial knobs. But, as Tim Watkins points out in Economic Chemotherapy, a five percent growth rate means that key metrics double over a 14-year period: twice the energy consumed, twice the minerals mined, twice the goods and services produced, twice the greenhouse gas emissions, twice the refuse going into landfill, and twice the debt.

The myopia concerning the physical world was discussed in a recent post by Tom Murphy, The Ball Comes to Rest. Murphy wonders why impressive thought leaders such as Ezra Klein do not seem to accept the fundamental importance of our physical predicaments.

I’ve often been impressed by Klein’s sharp insights on politics, yet can’t reconcile how someone so smart misses the big-picture perspectives . . . tons of sharp minds don’t seem to be at all concerned about planetary limits or metastatic modernity.

This brings me to the ultimate peril. As large, hungry, high-maintenance mammals on this planet, we are utterly dependent on a healthy, vibrant, biodiverse ecology—in ways we can’t begin to fathom. It’s beyond our meat-brain capacity to appreciate. Long-term survival at the hands of evolution has never once required cognitive comprehension of the myriad subtle relationships necessary for a stable community of life.

As I have said in previous posts, the original purpose of this substack was to evaluate technical responses to the climate crisis in order to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2050. It is evident by now that we are not going to achieve that goal, at least not voluntarily.

Yet we still need to look at new technologies in order to manage future transitions as efficiently as possible. The fact that so many of our leading writers seem not to fully understand the dilemmas we face is a concern and an obstacle.