A Clunky Sentence

Remarkable and Incomprehensible

Welcome to this series of newsletters on the theme Net Zero by 2050: Technology for a Changing Climate.

In response to the climate crisis, many business and industry leaders have committed their organizations to a ‘Net Zero’ program. By this they mean that their organization will not be emitting greenhouse gases by a specified date — often the year 2050. The purpose of these letters and posts is to help these leaders by providing realistic and practical information to do with net zero technologies. The emphasis is on the word ‘realistic’.

Please use the Subscribe button to keep up to date with our newsletters and posts. Additional information is provided at the Sutton Technical Books site and at our YouTube channel. The audio that accompanies this video is here.

The term ‘Net Zero by 2050’ has been adopted by organizations all over the world. It is also the theme of the posts at this site. Therefore, it is worth spending a few moments examining where the phrase came from and what it means.

The IPCC

The Net Zero story starts with the creation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in the year 1988. The IPCC is a United Nations body whose role is to provide policymakers with regular scientific assessments on the current state of knowledge about climate change. The IPCC does not conduct its own research; instead it compiles information from thousands of peer-reviewed published scientific papers.

In 2018 the IPCC published its best known and most important report: Global Warming of 1.5 °C. The report contains the following remarkable and incomprehensible sentence.

In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range).

< my emphasis >

The readability of this sentence is at the 24th grade level; in other words it is unreadable. Yet it is profoundly important. Of this sentence the journal Bloomberg Green said,

Like most statements the IPCC sets down, the most important sentence ever written is just terrible—clunky and jargon-filled. What it says, in English, is this: By 2030 the world needs to cut its carbon-dioxide pollution by 45%, and by midcentury reach “net-zero” emissions, meaning that any CO₂ still emitted would have to be drawn down in some way . . .

. . . it may turn out to be the grammatical unit that saved the world. If not, it'll be remembered as the last, best warning we ignored before it was too late.

Net Zero by 2050

The term ‘Net Zero by 2050’ was quickly adopted by a many governments, industries and even oil companies. Although there is nothing inherently special about the words ‘Zero’ or ‘2050’ they are pithy and memorable and they provide an easy-to-grasp target if only because they contain plenty of zeroes.

Also, the fact that the year 2050 is included in the phrase means that a deadline has been set. Addressing climate change is no longer something that needs to be taken care of in some indefinite future. 2050 is just 28 years from now — well within the lifetime of many people now living.

The use of the word ‘net’ means that organizations can continue to emit greenhouse gases as long as they remove an equivalent amount in some other way. In practice this means that they need to invest in Direct Air Capture (DAC) facilities.

For example, the aviation industry needs jet fuels if they are to continue to operate as they do now. Alternative fuels such as hydrogen and ammonia do not have the energy density needed to power an airplane that has the range and capacity of today’s jets. Therefore, airline companies are planning on building and operating DAC facilities that will remove the same amount of CO2 as their jet airplanes emit.

The year 2050 is, of course, an arbitrary deadline. The forces of nature have no interest in the targets that we create for ourselves. Mother Nature is going to do what she wants to do both before and after the year 2050. If we fail to “bend the curve” then the trends talked about will continue; the climate will continue to change and the consequences will become ever more calamitous.

Not Just CO2

The original sentence in the IPCC report refers to ‘anthropogenic CO2 emissions’. Carbon dioxide is indeed the most important greenhouse gas, but there are many others. Methane, in particular, warrants close attention. Depending on the amount of time it has been in the atmosphere its greenhouse potency is around 50 times that of CO2. Roughly 10% of the global warming that we currently experience is caused by methane. Natural gas is mostly methane, so any unburned gas adds to the methane load, as do fugitive leaks from natural gas operations. However, the methane that poses the greatest risk is that emitted from clathrates — natural releases from arctic permafrost. This phenomenon could create a tipping point, sometimes alluded as the “clathrate gun”.

The need to reduce methane emissions was one of the key resolutions coming out of the COP26 conference in the year 2021.

The Paris Agreement

The 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) was held in Paris in 2015. National leaders from all over the world created a unified policy and a legally binding treaty that is often referred to as the Paris Agreement. It called for countries to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C by the year 2020.

The mood at COP21 was optimistic. Nevertheless, the signatories to the Paris Agreement recognized that they were not likely to meet the targets that they had set, so they asked the IPCC to determine what actions would be needed to keep the temperature increase below 1.5°C by the year 2030. It was this request that led to creation of the Global Warming of 1.5°C report already alluded to. Many environmentalists criticize the report as being too conservative, i.e., as being too cautious. If this criticism is true then it does mean that those who use its analyses and projections cannot be accused of alarmism.

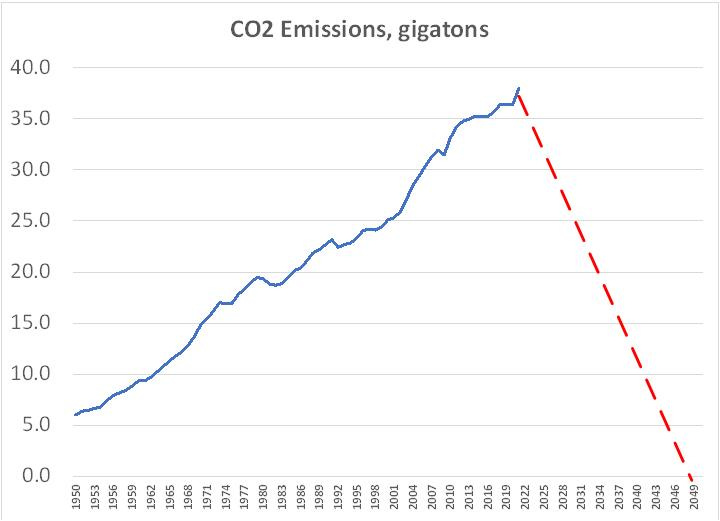

Six years have passed since the Paris meeting. COP26 was held in Glasgow in November 2021. (A year was skipped due to the pandemic.) The mood at COP26 was much more sober than it had been in Paris. The optimistic targets of 2015 were not met. As the graph shows, annual emissions of CO2 have steadily increased since the year 2015. Indeed, it appears as if the rate at which we are adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere is accelerating. The chances of reaching Net Zero by 2050 appear to be very slim unless radical changes are made.